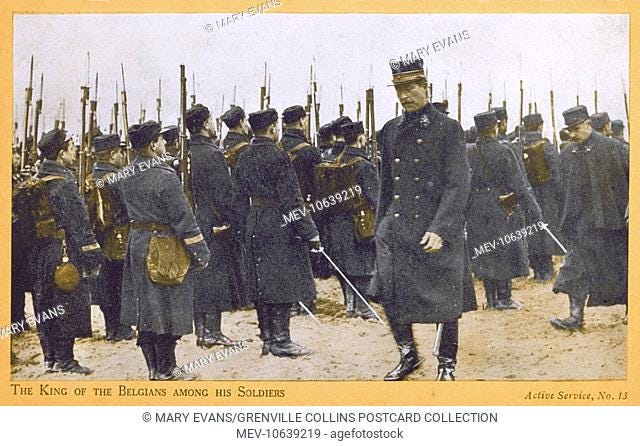

The Soldier King

How Albert I, king of Belgium and Knight of Columbus, led his country through one of its darkest hours with servant leadership

All Saints’ Day was a particularly solemn morning in the seaside town of De Panne, Belgium, Nov. 1, 1914. Since Aug. 4, the country suffered from immense turmoil and devastation due to a massive German invasion in the early months of World War I. Tens of thousands of lives were lost, and enemy forces captured more than 90 percent of Belgian territory.

After the siege of Antwerp, the weakened Belgian army retreated to the northwest coast beyond the Yser River to disrupt the German’s “race to the sea” and defend the last unoccupied stretch of their homeland; meanwhile, the Belgian government had been exiled to Le Havre, France, by mid-October.

Yet, the local parishioners at the 7:30 a.m., Mass in De Panne were joined by their country’s leader — King Albert I — who stayed in Belgium and shared in their suffering and resilience against overwhelming odds. That morning, with only one guard, the commander of the Belgian forces and his wife, Queen Elisabeth, had “no more of the artificial signs of kingship” as he sat in the pews with an “expression of a noble sorrow,” according to a Daily Mail dispatch.

The Belgian king often found solace from the front lines in the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate chapel, just as he had that morning. Only the day before had the German advance been halted due to the strategic flooding of the Yser River. The maneuver — decided by the king — would eventually prove vital in Belgium’s struggle for independence.

For his wartime efforts, King Albert I transformed from a monarch to an international hero with the popular moniker “the Soldier King,” while prominent political leaders such as Winston Churchill called him one of “the great liberators of the world,” at the time of the sovereign’s death. The Knights of Columbus recognized in Albert a man of virtue and commitment to the faith, bestowing an honorary membership on the king during his 1919 visit to the United States.

The faith steered King Albert’s conscience and servant leadership throughout his life, especially in one of the darkest hours of his country’s history. As he stated in his 1909 coronation speech: “The sovereign should be the servant of the law and the upholder of social peace. May God help me to fulfill this mission.”

A Call of Duty

Albert’s ascension to the throne was not a certainty. Born April 8, 1875, he was the second son of Prince Phillipe — the brother of King Leopold II. The monarch had a son and heir apparent, Leopold, Duke of Brabant, who died several years before Albert’s birth. The line of succession transferred to Phillipe and Albert’s older brother Baudoin of Flanders, however both died in 1905 and 1891, respectively. The inherited obligations of kingship fell on Albert who had no thirst for power, yet he dutifully and devotedly accepted the responsibilities.

The newly heir apparent had an inquisitive mind, often traveling incognito to other regions of Europe — under the pseudonym Mr. Albert Coburg — and even to the United States in 1898, soaking in the knowledge of trade, economics and even railways to later improve Belgium’s way of life.

He was also an attentive man, perhaps due to the religious education conducted every morning by his mother, Princess Mary of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. Nowhere is this attentiveness, and compassion, more evident than during his international 1909 trip to the Congo — then a Belgian colony — to investigate social unrest and cruel treatment of the natives, which greatly distressed him. For four months, and nearly 3,000 miles, then-Prince Albert listened to the plight of the Congolese, taking copious notes much to the consternation of his staff. In one instance, Albert was discovered squatting upon the ground before the hut of a native chief, writing down the man’s story. His outreach was popular among the Belgian colonials, reverently calling him the “Tall Man, Breaker of Stones.” This affinity of Albert, to be one with his people, was a precursor to his experience throughout the First World War.

The trip also serves as an example of his pursuit of reform. Upon his return from the Congo, Albert advocated for the advancement of medicine and technology in the region, stating in a speech, “It is in pursuing the moral elevation of the natives, in ameliorating their material situation, in combating the evils from which they suffer, and multiplying the ways of communication, that we will assure the future of the Congo.”

Albert, a former military cadet, ingratiated himself with his comrades and advocated for reforms, specifically in regard to military conscription. Prior to his ascension, members of the aristocracy avoided military service by paying a substitute to take their place. Albert spearheaded the campaign to abolish this practice. In a speech he delivered on Jan. 7, 1910, following the passage of the new form of conscription, Albert stated, “By suppressing the principle of pre-emption, all classes of society are now engaged equally in the performance of the same sacred duty, viz., the defense of our native land. For the future, a really national Army, both solid and numerous, will form for poor and rich alike a healthy school of patriotism. Belgium will be able to count on it for the preservation of her inviolable independence.”

The heir apparent was also conscious of the poor within his own country and focused his energies on improving their well-being. Along with Princess Elisabeth, the royal couple founded the Albert and Elisabeth Dispensary, which tended to the medical issues of those in need, and established an orphanage for children of Belgian fishermen who lost their lives. The prince was even known to respond to monetary requests from those in the working-class, generally those who were sick or incapable of working.

On Dec. 17, 1909, Albert’s uncle — King Leopold II — passed away. Only a few days later, Dec. 23, the unlikely heir apparent at the time of his birth was crowned king of Belgium. Always a man of innovation, Albert took the royal oath not only in French, but in Flemish — a first in the country’s history as an appeal for unification. In the antebellum years, the new king continued his charitable outreach, promotion of the arts and education, and quelled a potential workers’ strike by creating a commission to investigate their claims, all the while navigating the parliamentary politicking from various parties — instead acting in, what he believed, the best interest of the country.

The qualities the newly crowned king exhibited prior to his ascension would resurface and expand in Belgium’s greatest moment of strife.

‘Forward for Right, for Freedom’

Belgium was a neutral nation, avoiding entanglement in foreign wars since the policy’s establishment in 1831. However, the country reluctantly abandoned that stance when conflict was thrusted upon them in the summer of 1914. But it wasn’t without a lack of trying.

On the eve of war, Kaiser Wilhelm II — the ruler of the German empire — confided in his friend and distant relative, Albert I about France’s rapid military mobilization. He feared French expansion to recover Alsace Lorraine, while concurrently aspiring to expand his own empire. To him, war was inevitable. Albert attempted to persuade the Kaiser toward peace, but to no avail. In fact, Albert’s relative was gauging an alliance with Belgium if necessary; yet matters were complicated with an established Belgium-British friendship solidified by the Treaty of London 1839 — in summation, if Belgium were attacked, Britain would come to the country’s aid.

After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophia by a Serbian gunman on June 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Germany followed suit of its ally, with aims of enacting the Schlieffen Plan, a military tactic devised to counter a two-front war by rapidly eliminating France. The plan, however, accounted for German forces to move undisturbed through Luxembourg and Belgium.

King Albert realized an invasion by Germany was unavoidable, and on Aug. 2, the inevitable occurred: the German government issued an ultimatum to Belgium, demanding safe passage or suffer destruction. The Belgian government only had 12 hours to respond. Despite the German army positioned on their doorstep, Albert remained steadfast in the policy of neutrality, while he strengthened diplomatic ties to Britain.

The next day, Albert justified his stance of neutrality to a packed chamber in the Belgian Parliament, invoking loyalty to country and demand of independence:

“If, however, it is necessary for us to resist the invasion of our soil, that duty will find us armed and ready to make the greatest sacrifices. …This is the moment for action. …I have faith in our destinies. A country which defends itself wins the respect of all, and cannot perish. God be with us in this just cause.”

Belgium’s answer was not welcomed by the Kaiser. On Aug. 4, German forces crossed the Belgian border, sparking the Battle of Liège. Albert promptly placed himself at the front lines and as the head of the Belgian army, whose strength was vastly outnumbered and outgunned by Germany — an estimated 220,000 to nearly 1 million, respectively at the start of the conflict. Despite the army’s limitations, the Belgian forces were reportedly inspired to fight due to the sheer presence of their king, who mingled among the troops and repeatedly visited the field hospitals. On one occasion, Albert even dictated a letter on behalf of a wounded soldier whose only wish was to write home.

Yet the Belgian army’s courage could not withstand Germany’s power, with Liège and, eventually, nearly the majority of the country falling under its occupation. It pained Albert to see the destruction of his countrymen’s homes and Belgian landmarks, as well as the immense loss of life, but he continued resisting German demands of surrender. In retrospect, Belgium’s early stand affected the course of the First World War, giving France and Britain enough time to mobilize their militaries to aid Albert’s forces.

His most critical military decision throughout the war was the flooding of the Yser River, which stopped Germany’s advance and created the Yser Front. For four years, Albert soldiered on with his troops on the front lines, despite being under fire and attempted kidnappings from German forces. Even at the behest of his staff, Albert protested leaving his men, stating, “How can I call any risk unnecessary when my soldiers have to incur it?” His leadership was celebrated among the Belgian army and civilian population; in fact, the king and queen were so popular that German occupiers forbade the sale of the royal couple’s portrait throughout the duration of the war.

Ultimately, Albert’s ability to connect with his army and people through the grueling four years of war kept the nation’s spirits alive to fight. He had faith in his countrymen, even as the Belgian forces dwindled below 47,500. Yet, the army survived. This faith is more evident in a speech King Albert gave to the Belgian troops before leading an Anglo-Franco-Belgian offensive attack on the Germans in what is now known as the Fifth Battle of the Ypres:

“It is your duty to drive back the invader, who has been oppressing your brethren for the last four years. The hour is decisive. The Germans are retiring everywhere. Soldiers, show yourselves worthy of the sacred cause of our independence, worthy of our traditions, worthy of our race. Forward for right, for freedom, for glorious and immortal Belgium.”

The Belgian army responded, relentlessly pushing the German defenses back to recapture most of the occupied territory including Ostend and Bruges. By early October, the German government requested an armistice with the Allied powers and on Nov. 11, 1918, the war came to an end. On Nov. 22, the king who stayed with his people — apart from a brief trip to England for a royal wedding — fulfilled a dream he longed for throughout the war: to re-enter the capital city of Brussels.

The war had cost the lives of many Belgians as well as loss of 16 to 20 percent of the national wealth, but, with the valiant leadership of their king, they remained independent. Now, the ever-dutiful monarch turned his attention from the battlefield to the country’s reconstruction, a task which would consume the rest of his reign.

Reconstructing a Nation

Prior to his re-entry into Brussels, King Albert began to reshape his country by holding discussions at Loppem Castle in Zedelgem that led to universal suffrage for all men over 21, a cause the monarch long favored. This was an early indication of the king’s reconstruction efforts of Belgium and his outreach to the common folk in the post-war era.

One of his first actions was the creation of “The King Albert Fund,” which provided temporary housing for those whose homes were destroyed by the war. The king inspired his government to rebuild war victims’ homes with a higher degree of comfort than they had experienced before the war. His biography Albert the Brave: King of the Belgians offers a picture of his determination for proper housing, stating “that he made it a special rule that, if a claimant was not satisfied with the Commissioners’ decision [in the rejection of an application], he could take his petition to the King in person.” Only a few were ever taken to the king.

While leading efforts to rebuild the nation’s public works, industries, monetary system and administration in the Congo, and the newly acquired German colony Ruanda-Urundi, Albert also made it a priority to restore the destroyed architecture across the country to its original state, particularly a 13th century Catholic church in Nieuport. Additionally, he promoted the arts, science and literature to revive Belgian culture and innovation. This fascination with innovation — that had been instilled in the king as a young boy — was an impetus behind his 1919 visit to the United States. During this visit, Knights of Columbus Supreme Director William Larkin, who led the Order’s WWI efforts overseas, was one of a committee that conferred on Albert honorary membership in the Knights of Columbus.

Albert’s attention to his faith did not diminish in the post-war reconstruction, often visiting with missionaries from the Congo and all over the world. It also served as a foundation to his reign. . During a speech commemorating the dead of the Battle of the Yser, Dom Marie-Albert, abbot of Orval Abbey, quoted Albert, who reportedly said, “Every time society has distanced itself from the Gospel, which preached humility, fraternity and peace, the people have been unhappy, because the pagan civilization of ancient Rome, which they wanted to replace it with, is based only on pride and the abuse of force.”

Sadly, the king who aimed to improve his country’s well-being died during a rock-climbing accident on Feb. 17, 1934. He was 58 years old.

In an obituary published in the April 1934 issue of Columbia, the Knights of Columbus wrote, “The grief of the Catholics all over the world over King Albert’s death is deeply felt because, being faithful to his country and to himself, he was also faithful to God. Never was he accused of compromising his conscience, never was his loyalty questioned.”

It was his ability to remain committed to his values — imbued by his Catholic faith — that influenced Albert’s capacity to humbly and heroically guide his nation through one of its darkest hours, and rebuild Belgium with a charitable hand toward those who suffered.