Metropolis (1927) Review

What is Fritz Lang's silent classic, Metropolis (1927), trying to say with Christian imagery?

Earlier this week, the Shakespeare Globe tweeted, then quickly deleted, a soliloquy from the gender-bending play, I, Joan, which retells the story of the 15th century French military leader — who was martyred for the faith — as a transgender and/or non-binary woman. The Catholic-Twitterverse (yes, this subculture exists) rightly found the snippet offensive because the play misconstrues Joan’s insistence on wearing men’s clothing as conclusive of her queerness, and not for her actual reasons: to obey God’s order as she describes in trial documents, but also, more practically, protect her virginity (i.e. to avoid being raped!). Essentially the left is commandeering her martyrdom to progress issues that the saint — more than likely — would’ve found troublesome if alive today.

The minds behind I, Joan clearly see her as a valuable vessel as she well-known enough in popular culture. But this author — like many others — found their limited view of Joan’s saintly heroism misguided. However, the brief episode in the ongoing social media nonsense begs several questions: what happens when Christian characters and symbolism are utilized to achieve a political end that conflicts with the Church’s teachings? Or what happens when the Christian imagery becomes a mirage — devoid of its meaning or even God?

Which leads me to my latest movie viewing: Fritz Lang’s silent movie magnum opus, Metropolis.

The film is a technical achievement for its time. Massive doesn’t begin to describe the scale (which is sorely missed in cinema today). The science-fiction tale noticeably inspired the Los Angeles streets in Blade Runner (1982), C-3PO in Star Wars, even the Art Deco style of Batman (1989) and the subsequent animated series (side note: the third act in Tim Burton’s Batman is nearly identical to the third act in Lang’s Metropolis). For its audacity and German Expressionistic futurism, Metropolis is often considered one of the greatest movies of all time — even outside of its own era.

But films are more than special effects.

The plot follows the son of Metropolis’ leader, who descends from the upper-class lifestyle to improve the lives of the lower, working classes — who suffer underneath the earth — operating the machines that kept the city alive. The workers are a collective that move en masse and are subjugated to endless hours of torment, only to be easily replaced after a mishap. They are disposable. They lack human dignity. Even their children endure similar hardships. During a nightmare, the son — Freder Fredersen — envisions the workers, stripped of their clothes, being consumed by the hellish pagan god Moloch (which is more gut-wrenching as this predates the Holocaust by 10-15 years).

Freder pities their condition, unlike his father, and seeks to change it after hearing the words of a beautiful woman, Maria, who pleads with the wealthy in Metropolis’ equivalent for the Garden of Eden, “Look! These are your brothers.”

Sounds like a recipe for a Marxist sympathetic movie, yet Lang’s film is more complicated. While the workers are finally convinced to rebel against their oppressors and act on those revolutionary impulses, their actions are not rewarded — instead, they destroy a machine called the “Heart,” which, in a chain reaction, floods the undercity and nearly engulfs their children. The scenes are reminiscent of the French Revolution and even the 2020 riots. However, mob rule is scorned — and the mob realizes the consequences of their fervor only too late.

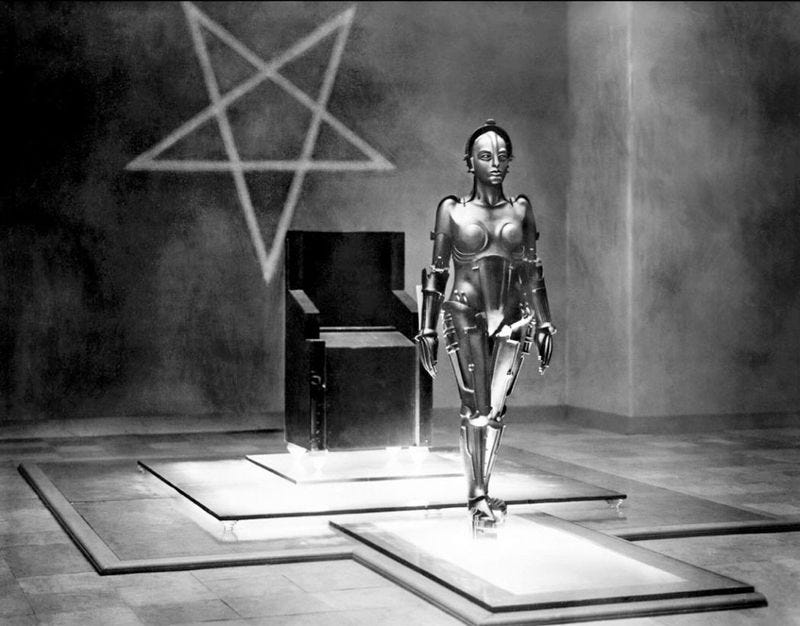

They lay blame for their actions at the feet of a “witch” — a robot doppelgänger of Maria created by a mad scientist (who looks like Doc Brown from Back to the Future). And yes, this robot is an evil character. The film, quite clearly, shows she is the embodiment of the Harlot from the Bible’s Book of Revelations. During one chaotic scene, the doppelgänger leads the seven deadly sins — who were initially statues at Metropolis’ cathedral — to ravage the spirits of society’s upper echelons.

This is not the only Christian imagery appearing in Lang’s magnum opus. Maria also holds sermons in the catacombs — an underbelly to the underbelly of Metropolis — in front of multiple crosses. She retells the destruction of the tower of Babel, although omits God’s intervention, which serves as a warning to vie for a peaceful solution rather than chaos. Even the exploited workers in the Babel parable and those in the catacombs are shot similarly, as well as the symbolic connections between Babel’s tower and Metropolis’ skyscraper. Maria concludes, “There can be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator.”

The workers long for a mediator — or a Messiah, perhaps? After the sermon, Freder approaches Maria saying she called him there, conjuring Biblical lines such as “Here I am, Lord” or “Behold, I am the handmaiden of the Lord.” After the grand finale, Maria acts as an intercessor — like how Mary, the mother of God, acted at Cana and continues to act on our behalf (if you believe in that which I do) — convincing Freder to join the hands of his father and the workers to coexist and live in harmony. Ultimately, the tower of Babel’s fate was avoided because a “heart” now exists between the “head” (Freder’s father) and the “hands” (workers).

The film predominantly relies on Christian imagery, but clearly this is a political movie to some extent — yet what ideological message was it trying to impart on audiences? Lang was not a Nazi sympathizer, emigrating from Germany after an interaction with Joseph Goebbels. However, his wife at the time — Thea von Harbou, who authored the book and screenplay — joined the Nazi party.

The class structure remains the same, so it isn’t Marxist. And the authoritarian-like leadership eases his rule, being convinced to do so by the son — so it’s not in support of fascism. Yet Metropolis was championed by both communists and fascists alike (more so the latter), and one can assume, after viewing it, the film wasn’t out to convert any souls to Christianity. Lang never explicitly mentioned that as his motive.

Ultimately, are the Christian symbols vapidly utilized, more so for recognition of a common Germanic heritage, rather than attempting to evoke Christ’s teachings? As mentioned above, Metropolis ends with the sides coming to a mutual, peaceful understanding — although the viewer never sees the utopia formed in the aftermath. So Christ is there, but to what extent. If the movie is an allegory of God’s relationship with Man, but reduces it to a more Humanistic conclusion, then does the film achieve its end of wanting audiences to find the human dignity in one another? Or is it the film equivalent of the Jeffersonian Bible — with the divinity and miracles ripped out.

Granted, Lang’s movie is not offensive like I, Joan. There is value in how the story ends. My point is filmmakers and writers often incorporate Christian imagery for the sake of achieving artistic depth — but removing or misunderstanding the symbolism imbued in the imagery and/or persons only reduces the impact or could make the creative effort meaningless entirely, even if intentionally used ironically.

….but if you need a recommendation, to borrow a phrase from my friend Stevie’s movie podcast, Metropolis is definitely worth a watch.