America’s Good Friday

The nation’s reaction to the death of Abraham Lincoln, 160 years ago.

*This article was originally published by Philanthropy Daily.

It was a Good Friday that shocked America.

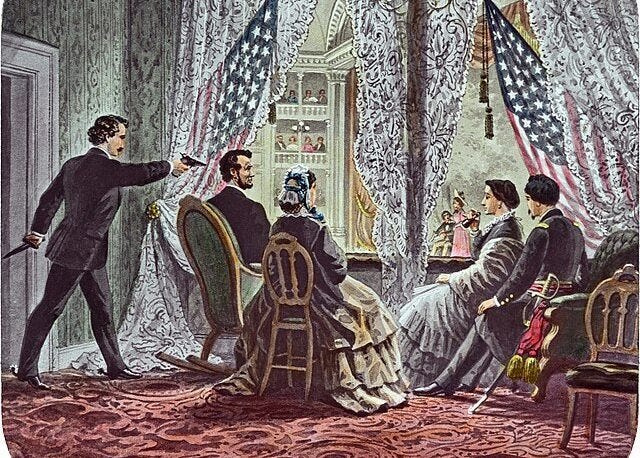

One hundred and sixty years ago, on April 14, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Lincoln’s death the following morning came mere days after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia, thus ending the Civil War, the bloodiest conflict in American history.

Lincoln—whose presidency coincided with the war’s full duration—had given his life to the cause of preserving the Union and, more importantly, ending slavery, freeing “not only of the millions now in bondage, but of unborn millions to come.”

The nation grieved over the loss of its “beloved Chief Magistrate.” Martha Hodes, author of Mourning Lincoln, writes that the assassination turned Easter Sunday from “what should have been a day of rejoicing over both the resurrection of Christ and military victory” into a solemn, sorrowful occasion.

Throughout his life, Lincoln’s relationship with the Almighty developed from one of religious skepticism to spiritual wrestling and exploration, to the point of being called the “theologian of American anguish.” In his article “God and Mr. Lincoln,” Michael Lucchese describes how the sixteenth president “did articulate a kind of theology of liberty, but it was always tempered by a humility born of suffering.” Even though in his younger years Lincoln famously utilized Christ’s “house divided’ sermon in a condemnation of slavery’s expansion, the Civil War ultimately “led him to a certain realization of the finitude of man and the infinitude of God,” as Lucchese states.

Indeed, Lincoln often reflected on “God’s will” amidst the bloodshed of Northern and Southern soldiers, writing, “God cannot be for and against the same thing at the same time.” The same is true in his Second Inaugural Address, which expands upon this meditation, climaxing with this call:

“Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’”

In short, he was a deeply spiritual man—and would have been chagrined at being compared to the Son of God. Nevertheless, on that Easter morning, many Americans drew parallels between Lincoln’s and Christ’s deaths.

On April 16, 1865, pews were packed across the United States, and “churches were all dressed in mourning, and every possible outward evidence was given to show how deeply Abraham Lincoln had enshrined himself in the hearts of the people,” as the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (April 17, 1865) reported. The paper continued:

“A strange sight it was to see all denominations assembled in their respective places, and bowed down with sorrow on the very day of all others when the Christian should feel happiest, when he reflects that a risen Saviour is his hope in a better world.”

Sermons could not avoid eulogizing the president. Phineas Densmore Gurley, pastor of New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in the nation’s capital, was one of many clergymen to address his death. Indeed, Lincoln attended services at the church—and his pew was left empty on Easter Sunday, covered with “black drapery,” as reported by the Daily Morning Chronicle (April 17, 1865). The pastor lamented “as the prospect of peace was brightly opening upon us” that a “sudden and temporary darkness” now hung over the country, yet he urged the congregation to “not be faithless, but believing” that “the morning has begun to dawn—the morning of a bright and glorious day, such as our country has never seen.”

Gurley was not alone in his reflection. Likewise, Rev. J.G. Butler from St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Washington, D.C., told parishioners that “Abraham Lincoln has been martyred, but the principles which he represented live, and will live forever.” Additionally, Rev. Francis Vinton of Trinity Church in New York City emphasized that Lincoln’s death was an important reminder that “the Lord Jesus alone was our President, our King, our Saviour.” However, he added:

“President Lincoln had arrived at the end of his mission. On the very day not only of our Lord’s crucifixion, but the day on which the raising of the flag over Sumter typified the resurrection of the nation, God had said to him, ‘Well done, thou good and faithful servant, enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.’ … As a nation, let us pray our Lord Jesus Christ to support him whom He has placed in the stead of the great and good man called to Himself. And with our lamentation let us mingle praise as becomes us on Easter Day.”

Others, unfortunately, were less generous in their comparisons of the circumstances of Christ and Lincoln’s deaths. The Chicago Tribune wrote, “The most horrid crime ever committed on this globe, since the wicked Jews crucified the Savior of mankind, was perpetrated by rebel emissaries, in the assassination of this great, wise, and good Abraham Lincoln.” They were not the only editorial to liken Southern sympathizers and “wicked” Jews—whose “blame” for Christ’s death has been, and must be, denounced in the centuries since.

Meanwhile, Americans—like the Daily Telegraph in Harrisburg, Pa.—called for “vengeance” against the South for Lincoln’s death. Moreover, as Lucchese emphasizes, “Radical Republicans sought to appropriate [Lincoln’s] legacy to justify their extreme plans for Reconstruction,” molding him into a “secular saint.”

Yet both courses of action miss Lincoln’s humility and most poignant message, which he stressed in his Second Inaugural Address:

“With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

If there is any lesson from Good Friday, both on Calvary and in Ford’s Theatre, it is that of the immeasurable spiritual fortitude and grace to forgive. From the cross, Christ showed mercy toward his persecutors by calling on God to forgive “for they know not what they do.” Lincoln, likewise, after the toil, destruction, and death from the Civil War, chose charity rather than retribution toward the Southern states. If the country had taken his course, perhaps the “cycle of violence” in the 160 ensuing years could have been avoided, whose “scars can still be witnessed across American society,” as Lucchese writes.

Ultimately, Good Friday is only “good” because of Christ’s mercy and resurrection on that glorious third day. Death’s sting was forever overcome. Yet, in some ways, America is still reeling from its “Good Friday,” April 14, 1865—but it would do us good to heed Lincoln’s spiritual growth and call for forgiveness, reconciliation, and charity toward neighbors.

Fondly should we hope, and fervently we should pray—and bind the wounds between brothers, sisters, families, friends, and countrymen.

Happy Easter!